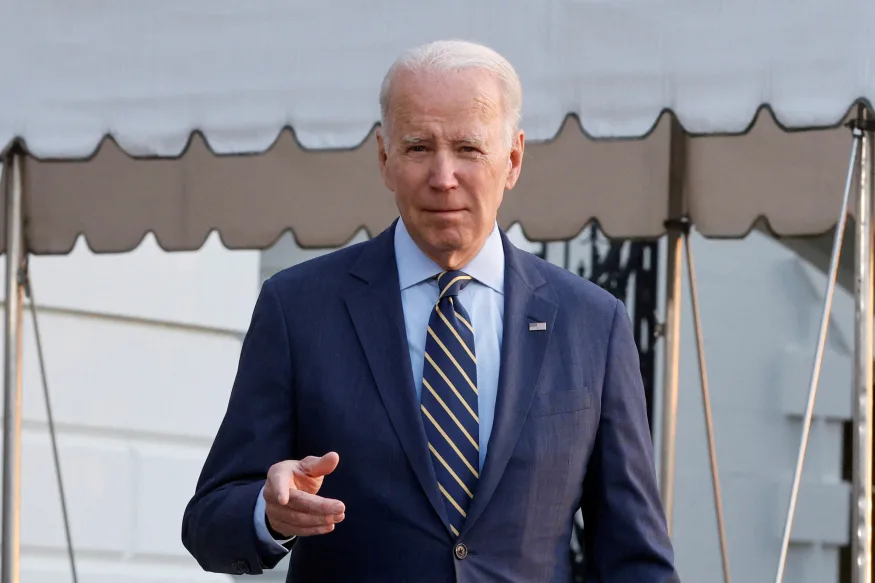

Biden calls for bipartisan legislation to keep Big Tech in check

January 20, 2023

Micrsoft announces 10,000 layoffs

January 20, 2023THE TECH WORLD’S biggest gadget show, CES, which took place in Las Vegas last week, looked a lot like a car show—and specifically an electric car show. Automakers and parts suppliers crowded the convention center halls with futuristic outlet-powered prototypes, sleek electric concepts, and software built to power that next generation of EVs. Yet the most vital electric auto project of the moment could hardly feel further from the limelight of Las Vegas.

Drivers are embracing electric vehicles faster than industry analysts had expected, and sales are booming. But those e-wheelers will need somewhere to charge up, creating an infrastructure problem much less glamorous than the latest electrified sports car.

Right now, some 90 percent of US electric vehicle owners can charge at home or at work. But convincing more Americans to buy electric is crucial (if not sufficient) to hitting climate goals. And more than a third of US residents live in apartment buildings, where installing a personal charger may not be an option. The US Department of Energy says there are just under 50,000 public electric vehicle chargers in the US, but one analysis projects that the country will need 495,000 if it hopes to hit state and federal goals to ban gas car sales by 2035. Each charger can cost more than $100,000 each to install.

The US government is throwing a lot of money at the charging problem, in a grand but low-profile national project. The bipartisan infrastructure bill passed in 2021 and last summer’s Inflation Reduction Act—a sneaky climate bill—together dedicate $7.5 billion to building electric-vehicle charging infrastructure on federal highways, and they provide millions in tax incentives that will make it cheaper for businesses to buy and install their own charging equipment. That’s projected to be enough to build half a million public chargers over the next five years. And in 2023, the government is set to send states $1.5 billion to build electric-vehicle charging stations along highways, with another $2.5 billion on the way for governments that want to build EV charging infrastructure elsewhere, with a special focus on rural and low-income areas.

Despite that cash injection, much is still unclear about how such a big and novel piece of infrastructure can be assembled, and how quickly. Getting public charging right will be crucial if the car-dependent US is to make an almost-pain-free transition to electric vehicles. That serious need, combined with a giant slug of federal greenbacks, means that the US’s EV charger project may be a generation-defining moment in the country’s climate journey.

Insiders hope the urgency and government programs can help the nascent charging industry get moving and become more standardized. It’s a welcome intervention in a space made even more confusing by the lack of consistency across charging points, which often can’t charge all EVs, vary in charging speed, and have problems with reliability.

Asaf Nagler, vice president of external affairs at ABB, a Swedish-Swiss company that builds and operates charging networks, calls the government help unifying. “It’s bringing people together to think about EV charging who may not have in the past,” he says. Government agencies, power utilities, automakers, and many others will all need to work together to make public charging networks ready to charge up everyone, everywhere.

Poor Service

Part of the challenge facing the US is that the chargers that do exist aren’t reliable. Driver complaints about broken public chargers are common, and horror stories about electricity-powered road trips gone awry capture plenty of headlines. Though it’s hard to track down firm data on how many chargers might be ready to top up an electric car at any time, one Bay Area survey found that one in four public fast chargers were down at any time.

The reasons are varied, but many are perhaps unsurprising for new technology left out in the elements. Cables break. Power electronics falter. Payment screens go dark. Vandals block charging ports. Wasps find unexpected new homes. “There’s a lot of discontent out there around how many chargers at a given point don’t work,” says Dave Mullaney, a principal with the research and advocacy group Rocky Mountain Institute, who studies mobility.

In some cases, companies that built and still operate early charging stations didn’t have to commit to maintaining them. Any that want to take part in new programs funded by the infrastructure bill will have to meet certain requirements for maintenance. What the standards for maintaining a charger should be is still being worked out by the federal government and the states that will build the projects. But any company that builds and operates a charger with federal money will have to submit detailed data on its use, reliability, and maintenance costs.

In fact, the federal government has required that states applying for public charger money submit plans detailing how they’ll support a new workforce to service them. “One of the biggest things we’re really excited about is the continued emphasis on reliability,” says Walter Thorn, head of product at ChargerHelp, which provides operations and maintenance services to charging companies and governments. The company is working with the Society of Automotive Engineers, an international standards body, to define what skills are needed to service chargers, and create certifications for them. It’s a first step in training up more electric-vehicle charger repairers.

Construction Crunch

In the meantime, plenty of chargers need to get into the ground. EVGo, one of the nation’s largest charging companies, says it currently has over 4,500 chargers in its engineering and construction pipeline, the most in its more than decade-long history. And right now, the process of putting in a new charger can take years.

Some of the delay comes down to a vital but snoozy issue: permitting. Fast chargers, which can refill a car’s battery in under an hour, require significant construction work. The process for getting them into the ground doesn’t vary much from place to place—it requires coordinating with utilities, digging trenches, and then installing the equipment.

But the process of getting permission to do that can be wildly different in every jurisdiction or city, experts say. Charging companies have called for a streamlined process that applies to lots of different places—one that could, for example, conduct an automated review for local safety and code compliance, the kind the Energy Department set up when it funded a similar solar panel program.

Meanwhile, pandemic-era shortages of electrical equipment, and especially transformers, have dragged on. “There’s a reason why you need to start early,” Matt Horton, CEO of the charging company Voltera, said in an interview last year. Getting even the most meticulously planned charger up and running can take longer than many governments, or EV owners, think.

Sustainable Effort

If the great American charging project is to succeed, companies need to know that there’ll be money in EV charging once the current federal money-fest is over. Although it may seem obvious that at some point EVs will be common enough that charging them can be good business, exactly when and how is unclear.

Companies that build or operate charging networks worry about competition from monopolistic public utilities, which can build their own chargers and in some states charge station operators significantly more for electricity at times of peak demand. There are also concerns that, despite the US government’s big spending, there may not be enough public funds to go around.

Chargers come with high fixed upfront costs, including real estate acquisition and construction. In places with relatively few electric vehicles, making back that investment could take a long time. States are required by the climate bill to build chargers along every 50 miles of highway, regardless of local EV traffic. “There’s a need for some help,” Jamie Hall, a senior strategist of EV policy at General Motors, said at an industry event in December. “The business case today for highway corridor fast charging can be tough.”

Some more optimistic industry observers see this as a short-term issue that can be resolved in the next half-decade or so—and before public funding runs out. Mullaney, the Rocky Mountain Institute analyst, says plenty of investment capital is flowing toward charging companies. The idea is that companies that can build out charging infrastructure now and get drivers accustomed to using it could reap profits from their loyalty for decades to come. “We’re nearing an inflection point where public charging is going to both really be needed, and also start making money,” he says. Hard work, in other words, can pay off.

Source: https://www.wired.com/story/people-love-electric-vehicles-now-comes-the-hard-part